OSMAN HAMDI BEY - TWO YOUNG WOMEN IN THE GREEN TOMB

OSMAN HAMDI BEY - TWO YOUNG WOMEN IN THE GREEN TOMB

OSMAN HAMDI BEY 1842-1910

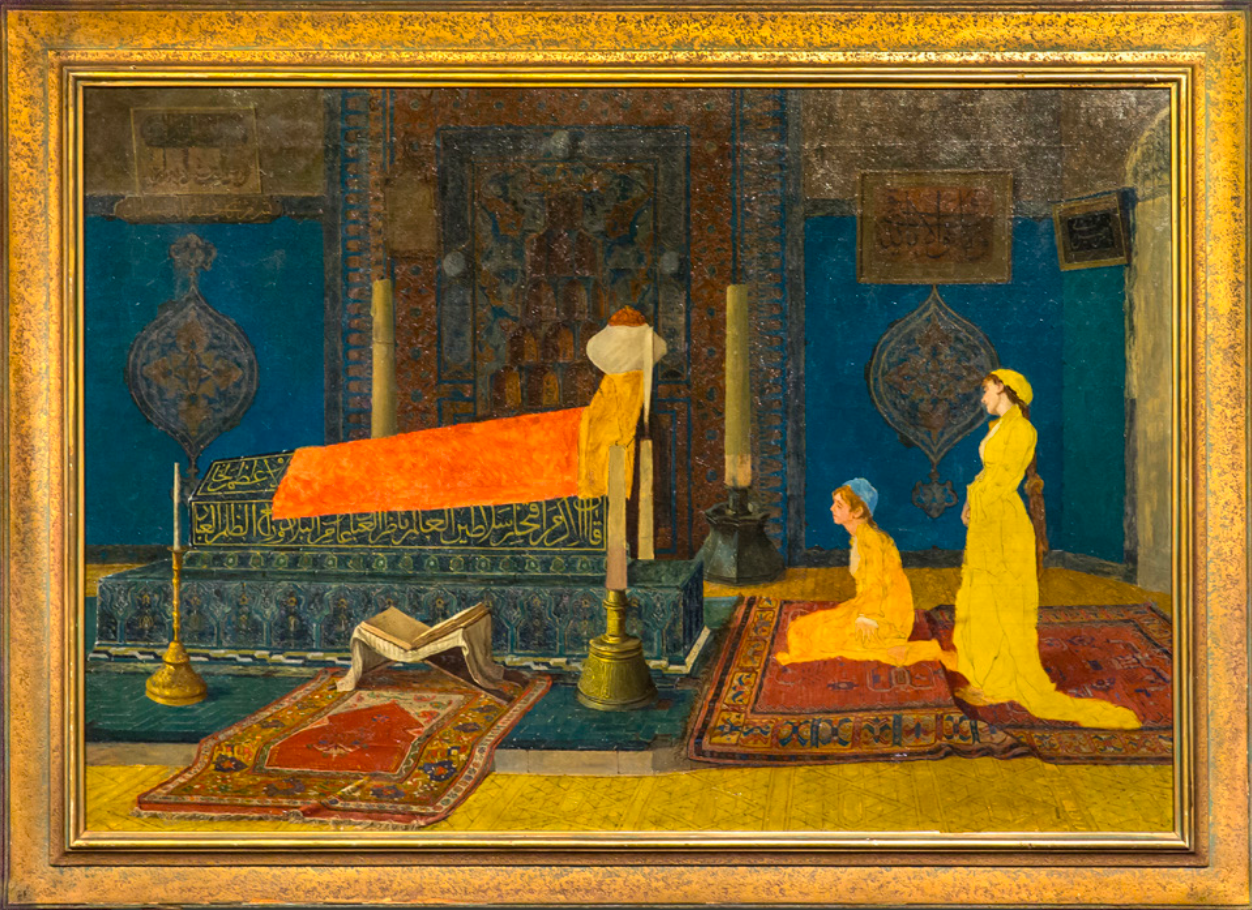

Two Young Women in the Green Tomb

1880s

Oil on canvas

76 x 111 cm

OSMAN HAMDI BEY 1842-1910

Osman Hamdi Bey, one of the founders of Turkish painting, was originally the son of a Greek father from Chios. Born in Istanbul, the artist began his primary education in Beşiktaş, then transferred to the Maarif-i Adliye. Despite his interest in painting, he was sent to Paris to study law upon his father's request. While studying law there, he also attended the School of Fine Arts. Here, he took painting lessons from the famous orientalist painter of the period, Gerome. He returned to Istanbul in 1869 from France, where he stayed for 12 years. The same year, he was appointed as the Provincial Director of Foreign Affairs in Baghdad. In 1873, he was tasked with taking the treasure to the Vienna Universal Exhibition. He contributed to the establishment of the Istanbul Archaeological Museum. He brought the Alexander Sarcophagus he found in the Sayda excavations to the museum. In 1883, he was appointed as the head of the school, taking the lead in the establishment of the School of Fine Arts.

Osman Hamdi Bey, who is also known as a man of culture, archaeologist and museum curator, brought the figure in composition to our contemporary art with an orientalist approach. His paintings developed in two main ways. However, he was especially evaluated as an orientalist painter both in Europe and Türkiye. The most important feature that distinguishes Osman Hamdi Bey from Western orientalists is that he did not have an oriental nostalgia like them but directly depicted his own cultural world, the places he lived in, the people and objects around him in his paintings. In these figures, who are dressed in Eastern clothes and reflect a workmanship specific to academic painting, the magnificent life and mystical philosophy of the Eastern world prevail. The basic feature of Osman Hamdi painting is to grasp the detail within a holistic order. In addition to his painting, Osman Hamdi Bey is a figure who left his mark on the 19th century Ottoman-Turkish art and culture world with his personality as an archaeologist, museum curator and educator.

---

The names given to Osman Hamdi’s paintings can vary considerably. This is because there are no records of the names he might have given to his works, other than those that have been exhibited in certain exhibitions. This is why the names of his paintings in this case have generally been determined by the art galleries or historians who have published or commented on them. Although it is obvious that this practice is inevitable, an important principle should always be kept in mind in this regard. That is, the name given should be as objective as possible, and therefore should be as true to the scene in the painting in question as possible and should not contain any comments that might give rise to discussion. This is why I found it appropriate to call the painting presented here as Two Young Women in the Green Tomb, which I think describes it most objectively. In this sense, I must admit that I ignored this principle myself when I gave the painting the name Two Young Girls in a Tomb Visit in the Osman Hamdi Bey Dictionary that I published in 2010. First of all, while it is certain that the tomb depicted is the tomb of Mehmed Çelebi (Mehmed I) in Bursa, known as the Green Tomb, it was a mistake not to reflect this very objective information in the title of the painting. On the contrary, although it is probably correct to assume that what the two women on the canvas are doing is a “visit”, it would still be healthier to reduce their relationship with the space to its simplest and most indisputable expression by saying “In the Green Tomb” since it is still a kind of reading of intention. In addition, it was of course unacceptable to describe these two women, who were clearly not children, as “young girls”. The only excuse I can put forward for these mistakes is that I have quoted the name in question as it is from Mustafa Cezar’s 1971 predecessor book on Osman Hamdi.

The name I suggested for the painting largely summarizes the scene that Osman Hamdi Bey transferred to the canvas. At the head of the coffin in the tomb built for Sultan Mehmed I (1386?-1421), also known as Çelebi Mehmed, shortly before his death, there are two women, one crouching and the other standing, both wearing yellow dresses and their heads lightly covered with a scarf. The standing woman's hair falls down her back in a long braid. None of the coffins known to be behind Mehmed's coffin, which belong to his three sons, four daughters and his nanny, are visible. The blue tiled wall behind the coffin and the mihrab in the middle are painted in vivid colors, but the ornamentation on the upper part of the mihrab is left out of the frame. The inscriptions, which constitute an important decorative element of the mihrab, were not processed by the painter. The euzu basmala on the outer frame of the mihrab then the 37th verse of the Al-i Imran chapter of the Quran and then a hadith about bowing and prostration He did not include the long inscription in the picture as it was, and was content with only giving the place of the hadith about visiting graves on the veil of the mihrab in an unclear manner.

It is not surprising that Osman Hamdi Bey did not transfer these inscriptions of the altar to the canvas. There is no doubt that the effort he would have made to render these long texts, written in a very complicated manner in a language he did not know, in a readable manner would not have contributed to the painting in terms of aesthetics. Of course, the color composition of the altar and the tiled wall was much more important to him. While the color provided by the tiles of the wall and the altar is in harmony with the color of the tiled coffin and the low tiled set on which it sits, the light brown of the plaster of the untiled part of the wall and the yellow of the mat spread on the floor and the women's dresses create a pleasant contrast. The cover on the coffin and the carpets spread on both sides provide the third color of the painting, red.

In addition to these main elements that make up the general decoration of the painting, Osman Hamdi Bey completed the scene he created by adding some objects in accordance with Islamic and Ottoman traditions, as he did in most of his paintings. A large Quran is opened on a thin cloth on a lectern standing at the head of the carpet spread in front of the coffin. There are two large candlesticks on each side of the mihrab, and two smaller candlesticks in front of the coffin with large candles. Three calligraphy panels hanging on the wall complete the scene. Although the size and detail of the one on the far right does not allow the inscription to be made out, the other two are quite legible. The one to the right of the mihrab bears the words “ve ma tevfîkî illâ billah”, meaning “my success is only with Allah” from the 88th verse of the Hud chapter of the Quran, written in celi sülüs calligraphy. Since this inscription appears in many of the painter’s paintings, it is possible to think that it is Osman Hamdi’s own addition rather than a plaque actually located in the tomb.

The inscription on the left of the mihrab is an interesting example that – as far as I could determine – does not appear in any of his other paintings. The upper line consists of a simple basmalah. Although the middle line is not clearly and distinctly drawn and cannot be understood, the lower line, written in Turkish, can be read quite easily and reveals the interesting nature of the inscription: “Tir-i müjgânı siyah idi anın”, or in simpler Turkish, “Karaydı her arrow-like eyelashes”. A plaque hanging on the wall of a tomb bears one of the typical metaphors used for the beloved in divan literature, “tir-i müjgân” (arrow-like eyelashes) It may be surprising to come across such an expression, moreover, in Turkish. The truth is that this expression is not taken from a love poem, but from a text known as hilye, which describes the Prophet's image and attributes. It is noteworthy that the hilye in which this expression is included, in contrast to the fact that it ignores the mihrab inscriptions completed by Hakani Mehmed Bey (?-1606) in 1007 AH (1598-1599) and is considered one of the main works that constitute the beginning of the hilye tradition in the Ottoman world, takes care to convey the large-lettered celi sülüs script decorating the visible facade of the coffin as it is. This inscription, which continues on the other side of the coffin, is in the nature of the tomb inscription of Sultan Mehmed I, who had the tomb built for himself. As might be guessed, this inscription, which consists of the name, lineage, date of death and exaggerated praise of the sultan buried there, starts on the visible side of the coffin here and continues on the other side, and is completed with a short prayer at the beginning. Osman Hamdi Bey, who showed us only one side of the coffin, had to represent only the first half of this inscription, but since almost the entire first line is hidden under the red cover placed on the coffin, it is not visible. He depicted the second line, which was exposed, quite well – probably thanks to a photograph – but made a surprising mistake at the end of the line, writing the last word as “el-ibad” instead of “el-fesad”, thus creating a strange expression meaning “dafi’ü-z-zulüm ve’l-ibad” (the one who destroys oppression and corruption) instead of “dafi’ü-z-zulüm ve’l-fesad” (the one who destroys oppression and corruption).

It is a poem of 12 couplets. The words that Osman Hamdi Bey transferred to this plate consist of the first line of the 284th couplet of this poem. Apart from the fact that it is not a common practice to convert a single line from a hilye written in long verse into a calligraphy plate, unlike the hilyes of later periods that were fitted onto a single plate, it seems impossible to guess why and how Osman Hamdi Bey, who did not have a traditional Islamic culture, chose this line.

It is noteworthy that the painter, in contrast to ignoring the mihrab inscriptions, took care to convey the large-lettered celi sülüs script that adorns the visible facade of the coffin as it is. This inscription, which continues on the other side of the coffin, is the tomb inscription of Sultan Mehmed I, who had the tomb built for himself. As might be guessed, this inscription, which consists of the name, lineage, date of death and exaggerated eulogy of the sultan buried there, starts on the visible face of the coffin here and continues on the other side, and is completed with a short prayer at the beginning. Osman Hamdi Bey, who showed us only one side of the coffin, had to represent only the first half of this inscription, but since almost the entire first line is hidden under the red cover placed on the coffin, it is not visible. He depicted the second line, which was exposed, quite well, probably thanks to a photograph, but he made a surprising mistake at the end of the line, writing the last word as “el-ibad” instead of “el-fesad”, thus creating a strange expression meaning “dafi’ü-z-zulüm ve’l-ibad” (the one who destroys oppression and corruption) instead of “dafi’ü-z-zulüm ve’l-fesad” (the one who destroys oppression and corruption).

It is difficult to decide whether this is due to ignorance or carelessness. This situation, which could be caused by something as simple as the word “Ibad” being written shorter than the word “fesad”, can be considered as an interesting indicator of the flexibility observed in Osman Hamdi Bey’s paintings in a more general way. The appearance of the inscription panels that we are not sure whether they are actually on the wall of the tomb or not, the writings that should have been on the mihrab being either illegible or not depicted at all, the placement of the Quran on a lectern around the coffin, the candlestick and the carpet, and of course the presence of two women at the head of the coffin, are all the results of the painter’s effort to create a scene. While it is possible to say that some of these are real, it is necessary to think that some of them were added or removed as a result of Osman Hamdi’s choice.

In order to get an idea about this, it is possible to compare the painting with two photographs that we have, which we can assume were taken at a somewhat later date, but at a more recent date. In one of these images, made by the famous Sébah et Joaillier studio, the interior of the tomb is not exactly from the angle seen in Osman Hamdi Bey's painting, but it gives a good idea of its order and appearance at that time. Unlike the painting, the other coffins are very well-looking, there are no calligraphy panels on the walls, there is no cover on the coffin and no carpet on the floor, the cap on the coffin is covered with a shawl. In contrast, although they are different from those in the painting, there are four candlesticks at the head of the coffin and a Quran lectern between them.

The angle of the second photograph, made by Abdullah Brothers, is very different, so the mihrab is not visible at all. However, as if confirming the other photograph, it is noteworthy that there is no cover on the coffin and no carpet on the floor, but the lectern and candlesticks are at the head of the coffin. The inscription, which is not clearly visible in the first photograph and leans against the head of the coffin, contains the identity of the buried person. The 12 quilts are exposed and completely match the shape in the painting. The most important addition in this photograph is the turbaned, bearded person kneeling in front of the Quran on the lectern at the head of the coffin. It is possible to assume that this person, who is clearly reading the Quran, was assigned to recite prayers for Çelebi Mehmed.

Of course, it should not be forgotten that the “mise-en-scene” risk I mentioned in Osman Hamdi Bey’s paintings is also a problem for photographers who generally address foreign clients, such as Sébah et Joaillier or Abdullah Brothers. It is possible to think that in both photographs, portable objects such as candlesticks and lecterns were placed for this purpose and were not actually present in that space, and that the person praying at the coffin or reading the Quran was posing to give the scene a “local” atmosphere and did not actually reflect the daily use of the tomb. However, apart from these common additions, the simplicity of the image in the photographs suggests that at least the calligraphy panels on the wall and the carpets on the floor were additions by Osman Hamdi Bey and were not actually in the tomb. The real clue that reveals these “creative” contributions of the painter is the frequent presence of these objects in his other paintings. Almost all of his canvases that use the interior of a mosque or tomb as decoration feature the same or similar types of candlesticks. But to give more specific examples, it would be sufficient to remind that the same plaque with the inscription “ve mâ tevfîkî illâ billah” is present in both the 1903 and 1908 versions of his painting Dervish in the Children’s Tomb, or that the carpet on which the two women stand on the right in the painting in question is an exact replica of the carpet displayed in his painting known today as Carpet Seller Acem, Acem Carpet Seller or Street Scene from Istanbul (1888) in Berlin.

The characters in the painting constitute an even more surprising dimension of this flexibility that we witness in objects. The presence of two women at the head of a coffin in a sultan’s tomb – or any tomb – is not an ordinary sight, to say the least. Moreover, the fact that these women’s heads are only slightly covered, one of them even has her hair flowing down her back, and that both of them are depicted in bright yellow dresses worn indoors is enough to show how far the painter has strayed from reality. It is also necessary to add a detail that those familiar with Osman Hamdi Bey’s paintings will immediately notice. That is, the women’s poses are repeated in other paintings where very different environments are staged. The most striking example of this is that the two women in this painting are identical to the poses of two of the four women in his painting From the Harem or Four Concubines (1880). Aside from the strangeness of depicting two women in home clothes in a tomb, the fact that these women are depicted in the same poses as the women in a harem scene is an obvious and striking indication of how flexible Osman Hamdi Bey could be when staging his paintings.

The fact that best demonstrates this attitude of the painter is the number and variety of his paintings in which he uses the same scene. As far as I have been able to determine to date, Osman Hamdi Bey – two of which have not yet been discovered but have photographs – has produced at least six paintings using the same setting and scene. We know of the painting, which is probably the first of the series and is dated 1881, only from a photograph taken by Sébah et Joaillier. This painting, which was included under number 170 in the ABC/Elifba exhibition that opened on April 8, 1881, was designed vertically , so only the head of the coffin and part of the altar are visible. A turbaned and bearded cleric kneels at the head of the coffin, reading a Quran from a lectern. Osman Hamdi Bey repeated the same scene twice in a horizontal format shortly afterwards. In the first of these (1882), A cleric wearing a yellow robe is praying by raising his hands while looking at the coffin. In the second one (1884), Again, a cleric in a yellow robe is reading the Quran standing at the head of the coffin, his hand to his temple, thinking. Both paintings are very similar to the painting we are examining here in terms of framing and angle; the differences are limited to the shapes and colors of the objects used, from calligraphy panels to carpets and from lecterns to covers. But of course, the main difference is that female visitors are depicted instead of male ones.

Interestingly, of the six paintings on the Green Tomb that we have identified so far, men are represented in half and women in the other half. Leaving aside what we have discussed here, a photograph points to the existence of a second painting that uses a similar composition. Although the date of this painting cannot be determined precisely due to the quality of the photograph, it is possible to guess that it dates to the early 1880s from the two eights. What makes this work particularly interesting, beyond the fact that a woman is represented, is that this woman's head is completely uncovered and she is wearing a western hat. The other "female" painting, which bears the date 1890, He uses the vertical format and framing of the “Hocalı” canvas of 1881, but stages the two women in almost the same poses as in the work we are considering here.

In Osman Hamdi's paintings, the tomb of Çelebi Sultan Mehmed, known as the Green Tomb in Bursa, is an interior space used in a very similar way to the Green Mosque. In fact, in the case of the Green Mosque, the observed variety of spaces - right or left sofa, view from inside or outside, the room with windows on the upper floor - or the differences in the layout - mosque, harem, bath - are not observed at all, and the interior of the tomb is always depicted from the same angle and with the same function.

When we examine these six paintings together, some important features of Osman Hamdi Bey’s painting strategy immediately stand out. The artist, who we know to have an orientalist style, essentially resorts to three main elements in order to leave an Oriental stamp on his paintings. The first of these is an interior that clearly evokes the Islamic or Ottoman past, which in this case is the Green Tomb. The second is the objects that are pleasing to the eye and compatible with the identity and atmosphere of the space: carpets, calligraphy panels, candlesticks, lecterns, etc. Finally, the third element is usually one or at most two “Oriental” people whose clothing is compatible with the decor and who give life and meaning to that space. What makes the painter not only an orientalist in form but also an orientalist in mind is that he chooses and constructs these elements as he wishes, and therefore, he thinks of the Orient as a template and plays with these three elements as he wishes in order to design it. Most of these manipulations are not very important. His decision to hang a calligraphy panel on the wall, his choice of carpets in certain colors and patterns, and the changing of the positions of the lecterns or candlesticks are choices that do not disrupt the integrity or consistency of the scene. However, his bringing one or two women to the forefront in a tomb actually creates a break with reality. It should not be forgotten, however, that Osman Hamdi Bey created his paintings with a Western audience in mind first and foremost. The fact that the first buyer of the 1882 painting was the British consul in Istanbul, William Henry Wrench, the American Elizabeth C. Hobson of the 1884 painting, and the French government of the 1890 painting is enough to remind us of this.

It is of course impossible to say anything definitive about the possible date of the painting. However, if we consider that he worked on this theme between 1881-1890, and mainly at the beginning of this period, it is possible to suggest that it was realized between 1881-1884. There is only one question left: Why the Green Tomb? It is known that Osman Hamdi Bey frequently used various architectural works in Bursa in his paintings. If the Green Mosque, whose entrance gate and various interiors he used, and the Muradiye Mosque, whose gate he frequently painted, hold an important place among these, then the Green Tomb completes the series of historical buildings that the painter drew inspiration from in the old capital. In this sense, it is not surprising that an artist who we know is so keen on depicting the details of Ottoman architecture in his paintings should have chosen one of the earliest and most impressive examples of this architectural style. It is certain that the presence of the most striking examples of Ottoman tile art inside this building – such as in the Green Mosque and Muradiye Mosque – attracted the painter, who was particularly skilled in depicting this decorative element.

But beyond these relatively abstract reasons, there is a very concrete reason why Osman Hamdi Bey used the Green Tomb so frequently in the 1880s. That is, the trip he made to Iznik and Bursa with the English lawyer and journalist Edwin Pears in May 1880. During this trip, which I had the opportunity to examine thanks to the notebooks of Osman Hamdi Bey found in the possession of Raika Akar and Raffi Portakal, Osman Hamdi Bey took notes and, more importantly, drew many of the architectural and decorative details he saw. Unfortunately, all of the written notes are about Iznik, while the drawings related to the Green Tomb consist of details from the muqarnas and inscriptions of the mihrab. Considering that the painter does not include these details of the mihrab in the painting and focuses more on its colors, it is impossible to say that these drawings are reflected on the canvas. In contrast, there are two drawings directly related to the Green Tomb painting series on two unrelated pages of the notebooks. Both of these drawings, both drawn in pencil in a very faint manner, show a figure kneeling in front of a coffin in one, and in the other, the same scene is seen in slightly more detail with the selection of the lectern and carpet.

It would of course be an exaggeration to describe these two small sketches, drawn in such a hasty and indistinct manner, as preparatory sketches for paintings about the Green Tomb. However, it must be admitted that the presence of these drawings in the pages of a notebook containing his travels to Iznik and Bursa is significant. The fact that Osman Hamdi Bey drew these pictures while he was still visiting the monuments of the city, or shortly after, in the heat of the moment, is an indisputable sign that the idea of turning these scenes into paintings had already appeared in his mind.

Dr. Edhem Eldem

Share